Self-discovery in an Honors Thesis on an International Crisis

Graduating senior finds her passion in analysis of world response to Russia’s annexation of Crimea

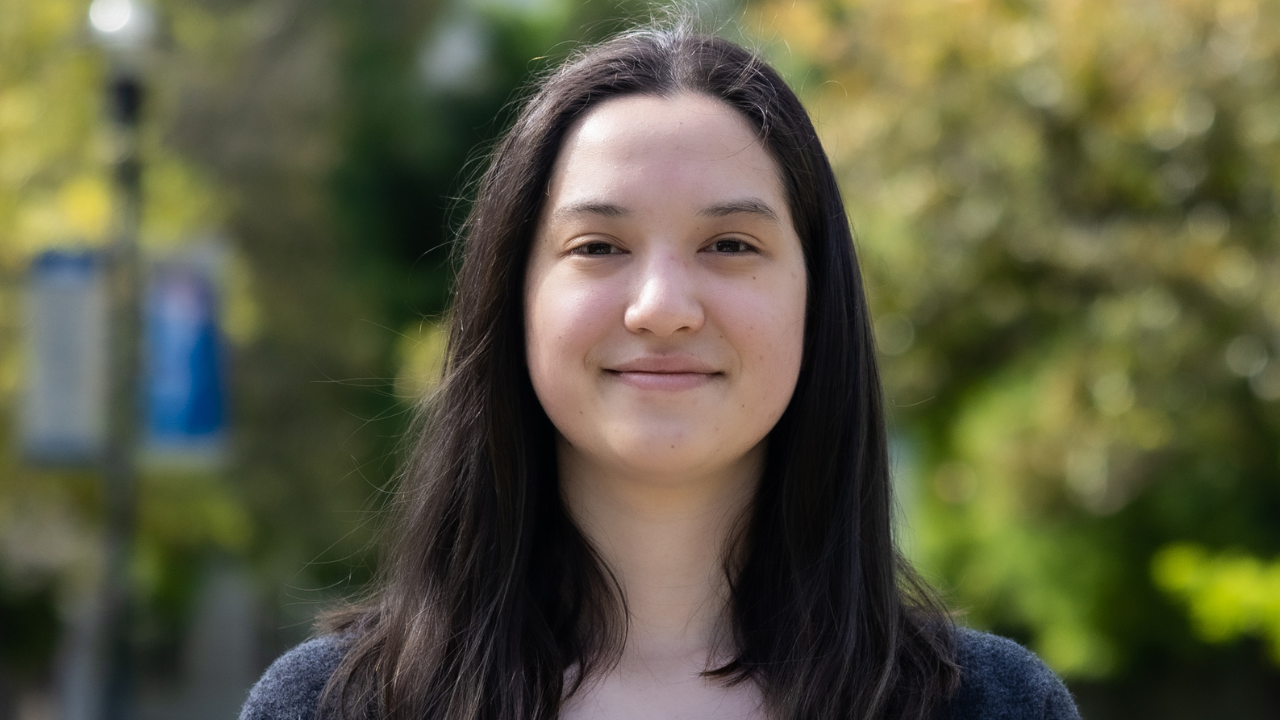

UC Davis undergraduate Quincy Kumfert was an aspiring scientist participating in a study abroad program in France in December 2021 when world events changed the course of her life.

Russia began amassing troops at the Ukraine border. In Kumfert’s class on European Union foreign and security policy, her professor and classmates debated whether the move was a bluff.

“The conventional wisdom was that people don’t just roll tanks over the border in Europe anymore” Kumfert said. “And yet, two months later, Russia invaded. The question, of course is, ‘Why?’”

Back at UC Davis, Kumfert, a double major in genetics and genomics and political science, became so intent on answering that question that she focused her honors thesis research on the international response to an earlier Russian incursion into Ukraine: its 2014 annexation of Crimea.

Analysis of a world crisis dataset

Kumfert used social network analysis of world political events to measure how other countries responded to the annexation in terms of cooperation or conflict with Russia. Social network analysis incorporates network and graph theory to investigate patterns of relations among people, organizations and states.

For her study, Kumfert obtained data from the Integrated Crisis and Early Warning System, a program supported by the U.S. Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency to monitor and forecast crises around the world.

Using an online, open-source software package created by her thesis advisor, Distinguished Professor of Political Science Zeev Maoz, Kumfert compared the level of cooperation and conflict directed at Russia by other states — as a measure of its prestige — over a 10-year span before and after it took over Crimea.

Her conclusion: The world inflicted no punishment on Russia. “Not only was there no cost, Russia actually increased in prestige after the annexation,” she said.

Professor Maoz said this reaction may have emboldened Russian President Vladimir Putin’s aggression towards Ukraine in 2022. He said Kumfert’s findings in her paper, “The Cost of Inaction: A Social Network Analysis of the Impact of the Annexation of Crimea on Russia’s Prestige,” hold important theoretical and policy-related implications.

“I have supervised over a dozen undergraduate honors thesis during my 20 years at UC Davis,” he said. “This thesis is by far the best I have seen. The level of insight, methodological sophistication, and innovative use of event-data compare favorably with most papers of our advanced graduate students.”

Professor Ethan Scheiner, who teaches top political science and international relations majors in his course POL/IRE194 “Honors Thesis Seminar,” also described the paper as exceptional.

“I don’t really believe in A-plus grades, but I gave her an A-plus because it was so far beyond anything I’ve ever received before from an undergrad,” said Scheiner, who joined UC Davis 19 years ago. “I had never met an undergrad before Quincy who could do network analysis. Very few grad students can do network analysis. I don’t know how to do network analysis.”

Looking beyond economic sanctions

While other studies have looked at how sanctions hurt Russia’s economy, Kumfert found none using network analysis to measure impacts on its global status or military strategy.

“If you only look at dollar cost, it doesn’t account for strategic costs,” she said. “I used a data set that looks at events: who did what to whom, when and how much — both economic interactions such as trade agreements, intentions to agree, but also strategic interactions. I did this is to be able to account for this comprehensive cost.

“I wanted to understand why Russia’s war calculus deemed the cause of invasion acceptable, that the benefits outweigh the costs. Was there a cost? Was there some sort of international backlash? Was there some sort of deterrence against future direct aggression?” she added.

Looking specifically at reactions of the U.S. and China, she found a few dips in U.S. cooperation with Russia from 2014 to 2019. “The U.S. made statements condemning these actions and imposed sanctions, but it didn’t tangibly decrease cooperation over the long period,” she said.

Chinese-Russian cooperation, on the other hand, spiked — possibly undermining the effectiveness of travel bans, trade restrictions and other sanctions imposed by the U.S. and other countries. “In cooperating with Russia, China may have acted as a kind of sanctions buster,” Kumfert said.

Princeton-bound for graduate studies

For Kumfert, her thesis project also resolved a personal dilemma: what career path to pursue after graduating this June.

Growing up in the east San Francisco Bay Area, the daughter of a computer scientist and a molecular biologist, she envisioned herself as a biologist and started UC Davis as a genetics and genomics major.

But she also took political science courses, after discovering her senior year at Amador Valley High School in Pleasanton that she liked civics. Soon, Kumfert had enough credits for a minor, and eventually a second major. “That introduced a little bit of an identity crisis,” she said.

To find her passion, Kumfert explored opportunities in both fields — working in a genetics lab on campus, participating in public health research, taking data science courses and signing up for a mentor-mentee program offered by the Undergraduate Research Center for students in the social sciences and humanities. That program paired her with a psychology graduate student, who gave her tips on finding a faculty research mentor to match her interests.

That led her to Maoz, whose areas of research include network analysis of international politics, international conflict management and resolution, and foreign policy decision-making. Kumfert took one of his courses, regularly attended office hours, and then — choosing political science over genetics for her honors thesis — asked him to be her thesis advisor.

“My entire undergraduate experience had been plagued by this existential question of not even what do I want to do, but what domain — STEM versus social sciences — do I want to pursue?” she said. “The thesis gave me clarity because once I started working on it, it was all I wanted to do.”

Her parents helped her recognize her calling, she said. “When I was talking about my thesis [they said], ‘We can see the light in your eye that wasn't always there. It sounds very clear what you should do.’”

Next fall, Kumfert will take the next step on that path, starting a graduate program in politics at Princeton University, with aspirations of someday becoming a professor.

— Kathleen Holder, content strategist in the UC Davis College of Letters and Science