In the last 50 years, the field of ethnic studies has become a core part of higher education. Across the United States, academic programs like the African American and African Studies, Asian American Studies, Native American Studies, and Chicana and Chicano Studies departments at UC Davis prepare students to critically engage a globally interconnected world.

Ethnic studies draws on diverse modes of inquiry, from the social sciences to the humanities, to historicize how social forces form ethnicities, and to better understand how such ethnicities intersect with other social formations to impact individuals and groups. The field endeavors to expand and diversify knowledge by cultivating the voices of underrepresented peoples. Ethnic studies research seeks to develop a practice of social critique, one that can take on social structures and institutions, which may at first appear moral, normal, or scientific, and submit them to critical reflection in the context of social conditions.

As UC Davis ethnic studies departments are marking half a century of groundbreaking teaching and research, the University of California community is offered the opportunity to better understand this rich and diverse field. Understanding the past not only helps one understand the role of ethnic studies at UC Davis today, but it allows one to see how these innovative programs continue to shape the university.

See an online version of an exhibition about UC Davis ethnic studies programs.

Born of a revolution

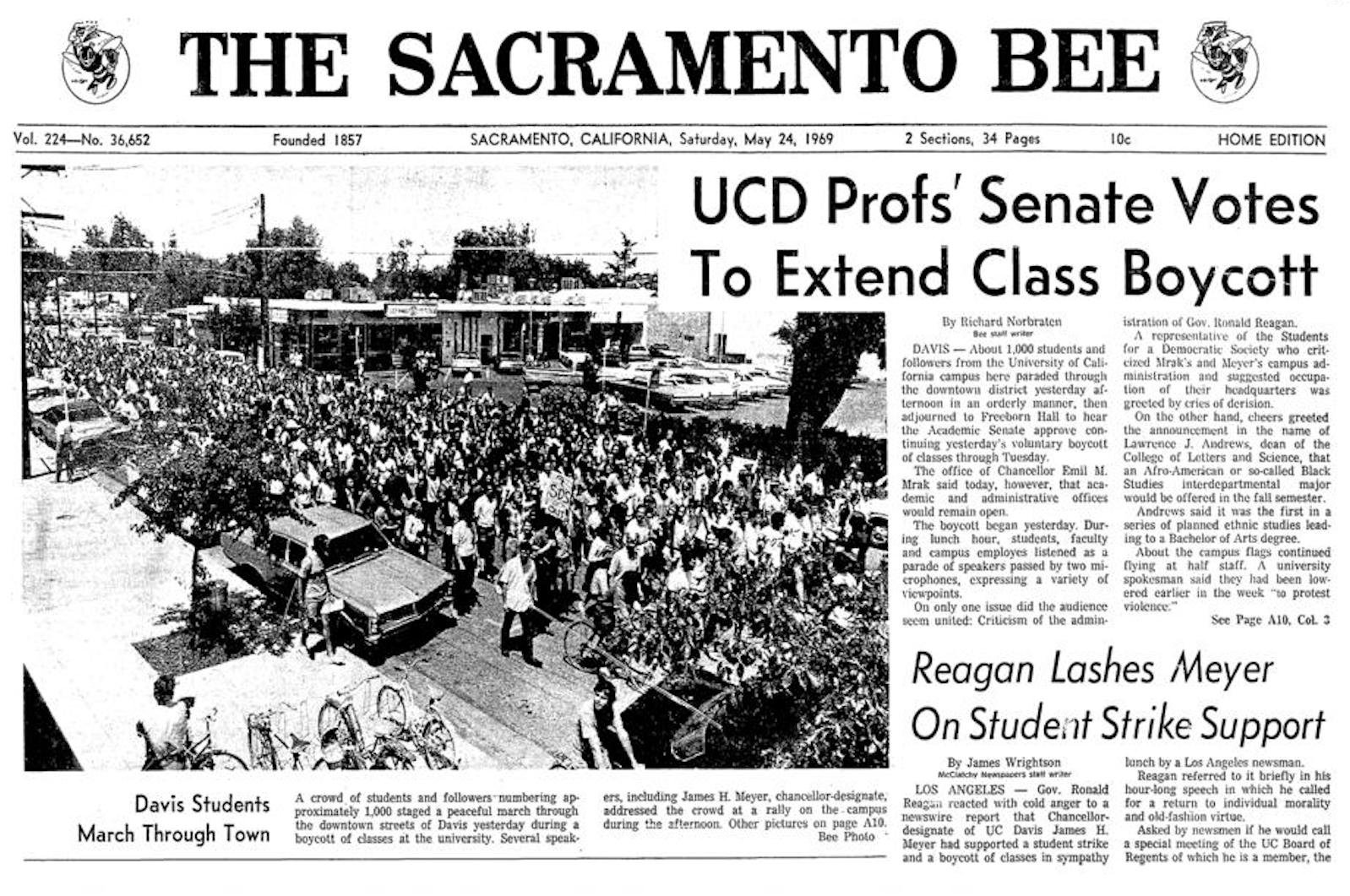

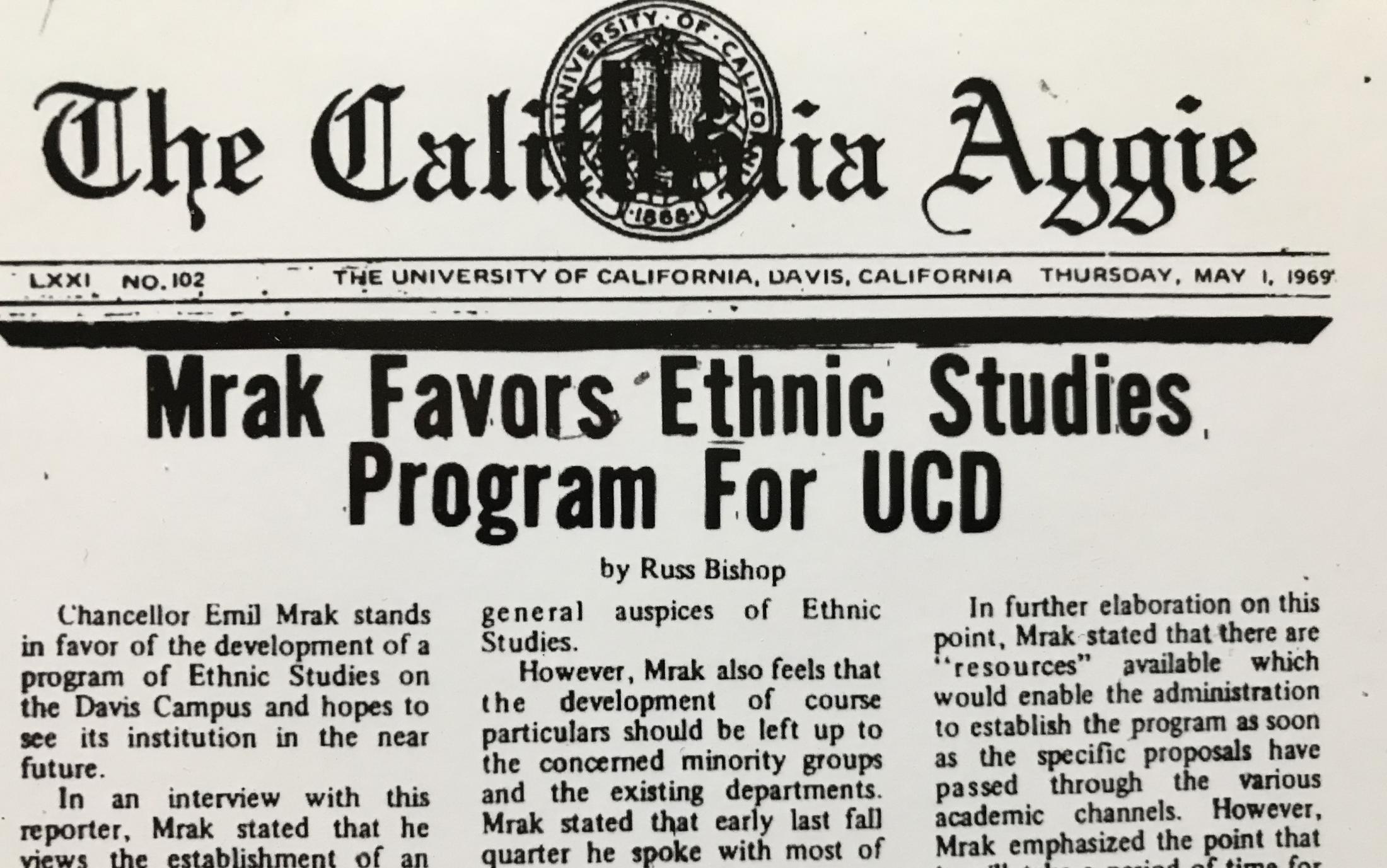

Ethnic studies was born in the political and cultural revolution that gripped UC Davis, the UC system, and many other universities in the 1960s. Paging through The California Aggie student newspaper, one gets a graphic sense of how much decolonization, civil rights, anti-war protests, the fight for women’s rights, and other liberation movements occupied student life. For an increasing number of students and faculty, university education appeared, at best, out of step with the challenges of contemporary life, and at worst, complicit in a system of oppression that connected neocolonial military adventures with segregation, inequality, domestic violence, and other forms of repression.

In cities around the world, students and like-minded faculty took to the streets to demand more from their governments and their universities. They petitioned for greater access to education, for the development of a university curriculum more accountable to the historical record, and for better administrative support for research programs equipped to critically engage power relations built on centuries of slavery, class war, colonization, and patriarchy.

California at the lead

California’s colleges and universities feature prominently in the foundation of ethnic studies. At San Francisco State University and UC Berkeley, student groups such as the Third World Liberation Front (TWLF) organized student strikes in 1968 to communicate the necessity of curricular reform and greater student diversity.

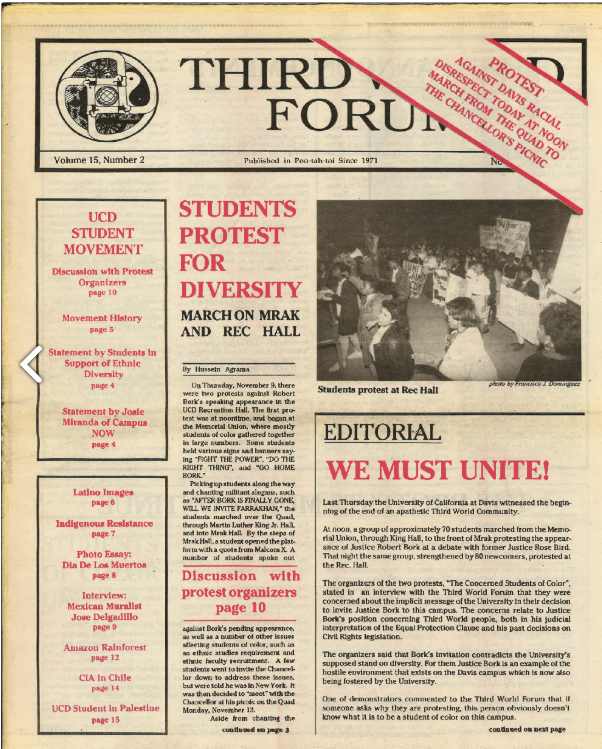

In those years, UC Davis students organized their own TWLF chapter and published Third World Forum, a newspaper, which worked to connect events at UC Davis to the growing social justice movements. Students at UC Davis also formed the Black Student Union, Asian American Concern, the United Mexican American Students, and the Native American Student Association. These groups staged symposia, published newsletters, and challenged the status quo by developing new relationships between the university and the community it was intended to serve.

On May 23, 1969, the urgent need for reform took center stage at UC Davis. During a UC-wide student strike, called to protest the presence of the National Guard at UC Berkeley, several student groups presented their demands for ethnic studies to new Chancellor James Meyer. About 5,000 people took part in the march and protest.

Documents in University Archives show these demands were highly articulated and detailed, including budgets and proposed course offerings. A review of campus events at the time also explains the focus given to community engagement and alternative futures. Concern was also expressed about the gap between the university’s research projects and its calling as a public university. Widespread structural unemployment caused by technology developed at UC Davis, such as the tomato harvester, led to an existential crisis for the university. By serving industry owners only, could UC Davis live up to its land-grant mission: to pursue science and knowledge in service of the public?

Faculty support for changes

The students’ call for deeper connections between the university and the public resonated strongly with professors like Isao Fujimoto and Jack D. Forbes, who became early allies and mentors for the student groups. Working in the applied behavioral sciences program within the School of Agriculture, they conducted research on the effects of industrialization on farm workers and other communities. Another ally was Emil Mrak, chancellor from 1959 to 1969, who supported the students’ plan for ethnic studies.

The development of ethnic studies at UC Davis was seen as a fulfillment of the university's commitment to the land-grant mission. For this reason, the first courses were offered in the School of Agriculture, rather than the College of Letters and Science where they are today.

Fifty years after their formation and the articulation of a vision by student and faculty activists, the ethnic studies departments at UC Davis continue to develop practices of cultural understanding and social critique. As relevant as ever, they play an important role in the university's renewed efforts to produce community-engaged scholars, and to cultivate knowledge in service of the public.

– David Michalski, social and cultural studies librarian, UC Davis Library