Belinda Martineau, a former genetic engineer and UC Davis Institute for Social Sciences (ISS) grant writer, was one of four experts invited by the UC Global Food Initiative to participate in a panel discussion, "GMOs: All Facts, No Fiction,” on two consecutive evenings at UC Davis and UC Riverside in November 2015. In a follow-up interview, Ben Hinshaw of ISS talked to Martineau about her background in GE food and her thoughts on what consumers deserve to know.

You are currently a grant writer for the Institute for Social Sciences at UC Davis. How did you come to be invited to speak at these UC Global Food Initiative events?

I am a molecular geneticist by training and a former agricultural genetic engineer by trade; I helped bring the world’s first commercialized genetically engineered (GE) food, Calgene Inc.’s Flavr SavrTM tomato, to market. I retired from bench science soon thereafter (when I was pregnant with my second child) and spent the next nearly two decades as a (natural) science writer and editor, the last eight of which as a principal editor 50 percent time with the UC Davis Genome Center. But when my children had both gone off to college and I no longer had a good excuse to not work full time, I applied for the grant writer position at ISS.

One thing I have learned from the public debate over GMOs during the last 20 years is that it takes more than just the details of a technology to bring the products of that technology to market. It also takes information about human behavior, political systems, ethics, economics, history, communication strategies, etc. — in short, the social sciences.

Additionally, I really enjoy learning about all of the interesting and important research that is being done in the Division of Social Sciences [in the UC Davis College of Letters and Science].

Nevertheless, over the years, I continued to follow developments associated with agricultural biotechnology closely. I wrote a book about bringing the Flavr Savr tomato to market: First Fruit: The Creation of the Flavr SavrTM Tomato and the Birth of Biotech Food (McGraw-Hill, 2001).

And, because I think societies need to know all the details about the science underlying a new technology like crop genetic engineering in order to decide how to most safely, effectively and sustainably utilize it, I started a blog (Biotech Salon) a few years ago to bring to light some of the facts about agricultural biotechnology that I felt some of the more ardent supporters of the technology were neglecting to mention.

What sort of “facts” are you referring to? What are GE proponents not telling us about so-called GMOs?

One often hears about how precise genetic engineering is, but not about its imprecise attributes — like the fact that genetic engineers have no control over where in a plant’s genome their foreign genes will land and that those genes often (27–63 percent of the time)  land in one of the recipient plant’s genes, in which case that plant gene becomes mutated.

land in one of the recipient plant’s genes, in which case that plant gene becomes mutated.

As another example, when using one of the two primary techniques for inserting foreign genes into crop plants, considerably more DNA than what is meant to be inserted can sometimes (20 percent of the time) become inserted into the recipient plant. This fact, which colleagues of mine at Calgene and I published in 1994, was particularly shocking to me because we had assumed that the insertion of such extra DNA would not occur and we had only looked for the additional DNA because scientists at the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) asked us to do so.

Additionally, it is a fact that the “coordinated framework” for regulating GE crops and foods in anticipation of commercializing them in the U.S. has so many loopholes that it is possible (depending on how a GE food crop has been designed) to bring a GE food to market without FDA, USDA or EPA regulation.

Thankfully, the Office of Science and Technology Policy in the Executive Office of the President, together with the FDA, have put together a committee to clarify “current roles and responsibilities described in the coordinated framework for the regulation of biotechnology and [develop] a long-term strategy for the regulation of the products of biotechnology." Hopefully, the U.S. system for regulating the products of genetic engineering will be vastly improved upon as a result of that committee’s work.

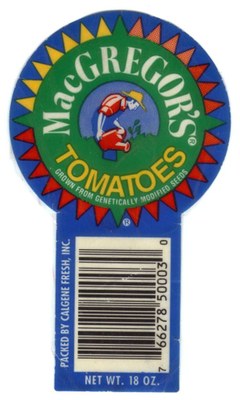

You mentioned your work with the GE Flavr SavrTM tomato, a product that was labeled in grocery stores as “Grown from Genetically Modified Seeds.” How do you believe GE products should be labeled? Is there sufficient regulation on this front?

When it comes to GE crops and foods, I feel that there is—generally—not sufficient regulation in the United States. I also believe that GE products should be labeled because:

- U.S. companies currently have to label their GE crops and foods in order to sell them in the more than 60 countries around the world which require those products to be labeled.

- The vast majority of Americans (80–90 percent) have indicated that they want GE foods labeled.

- In a democratic, capitalist society like ours, consumers should get to “vote” for new products with their pocketbooks and labeling GE foods would give them the chance to do that.

The Flavr Savr tomato also serves as a great case study for GE foods on the issue of labeling. First, because a foreign protein (which conveys resistance to the antibiotic kanamycin) was produced in Flavr Savr tomatoes, the FDA used the food additive provisions of the Federal Food, Drug & Cosmetic Act to regulate that GE protein as a food additive, and I believe those same provisions could be used to enforce labeling of foods containing GE additives. However, although most of the GE crops commercialized since the Flavr Savr tomato also produce foreign GE proteins, the FDA has not similarly regulated any of them as food additives.

The Flavr Savr tomato also serves as a great case study for GE foods on the issue of labeling. First, because a foreign protein (which conveys resistance to the antibiotic kanamycin) was produced in Flavr Savr tomatoes, the FDA used the food additive provisions of the Federal Food, Drug & Cosmetic Act to regulate that GE protein as a food additive, and I believe those same provisions could be used to enforce labeling of foods containing GE additives. However, although most of the GE crops commercialized since the Flavr Savr tomato also produce foreign GE proteins, the FDA has not similarly regulated any of them as food additives.

Second, Flavr Savr tomatoes (or rather MacGREGOR’SRtomatoes, Calgene’s premium Flavr Savrs), despite being labeled “Grown From Genetically Modified Seeds,” were very well received by consumers. The grocer who carried them here in Davis resorted to rationing them; one could only purchase two MacGREGOR’S tomatoes per person per day when supplies were limited, and he sold gift boxes of them during the 1994–95 holiday season. Another early GE-labeled food product, a canned tomato paste, also sold well in Great Britain in the mid-1990s.

Based on the reception these GE tomato products received, labels on GE foods can simply serve as information consumers want and—I believe—should have the right to know, and not necessarily as some kind of warning.

As for whether those labels should be based on the specific food additive(s) that a GE food contains, or more generally inform consumers that the process of genetic engineering was used to create the product they are considering the purchase of, I am still on the fence.

But I am definitely for labeling GE foods because I believe that improving transparency about the products of this powerful technology is one of the only ways to (re)instill public confidence in them.

Learn more

Read a summary of the panel discussion at UC Riverside.

Watch a video of "GMOs: All Facts, No Fiction."